The economic crisis has been the main topic of discussion for a few years in the European Union. Apart from sovereign debt and the financial aspect, there are three other fundamental dimensions to the crisis that Europeans must resolve: The political and social dimensions, and the question of competitiveness.

The Competitiveness Dimension

Europe’s struggle to remain competitive starts with the peripheral countries in the south and east of the European Union, which are not as dynamic as the north or the manufacturing bases that have emerged in Asia over the past decade. However, we’re also seeing a slowdown of Europe’s core economies — Germany and France — coupled with an increase in unemployment, particularly youth unemployment, all over Europe.

The Political Dimension

Because the EU is not a federation, but a collection of nation-states bound by international treaties, we’re seeing increasing tensions within the decision-making process. Most of the policies emanating from Brussels to mitigate the effects of the crisis involve the transfer of sovereignty to a supranational entity and, because of their supranational nature, these policies often generate political discord between countries (as they seek to protect their national interests) and within countries(within national governments or among populations). Austerity measures and the general economic slowdown are generating an increase in social discontent that threatens traditional parties’ longstanding hold on power and that strengthens anti-establishment parties on the left and the right.

The Social Dimension

The rise in youth unemployment has a negative impact not only on productivity, but also on the long-term development of national economies. Further, judging by the riots taking place in Sweden last week and those that affected France last year, unemployment can increasingly be linked to security risks that national governments must address. While social security systems are still important safety nets ensuring social stability, they are increasingly strained as the current crisis develops long-lasting negative effects on the European population.

The rise in youth unemployment has a negative impact not only on productivity, but also on the long-term development of national economies. Further, judging by the riots taking place in Sweden last week and those that affected France last year, unemployment can increasingly be linked to security risks that national governments must address. While social security systems are still important safety nets ensuring social stability, they are increasingly strained as the current crisis develops long-lasting negative effects on the European population.

Structures and Solutions

Not being a federation, what the European Union does have is unified regulation — it established the common market, a currency union, and other examples of what can be seen as coordinated economic policies. However, despite efforts to unify and coordinate economic policies across Europe, there remain vast differences in competitiveness within the European Union. Due to the current crisis, the eurozone has started a process of institutional reform, adapting to problems related to fiscal policies within the currency union and attempting to solve them. Reform measures under this rubric include the creation of the European Stability Mechanism, a permanent rescue fund for members in need, and granting the European Central Bank more power to intervene in bond markets to assist countries in distress.

This is a reactionary process of institutionalization that may or may not hold in the long term. — One concern is that the voices of those who will eventually need to join the eurozone have not been heard — and they have not been asked to share their opinions. For their part, these countries are showing less interest in joining.

The eurozone’s very method of operating — in which the European Central Bank controls monetary policy — has created problems for the member states in difficulty. In the past, the economies of the eurozone’s south could implement monetary policies to address their lack of competitiveness. With that option no longer available, the alternative is fiscal policy — which over the past few years has taken the form of painful austerity measures — and wage suppression. Addressing the crisis at the European level (rather than at the national level) is difficult since the centralized monetary policy is not yet coupled with a strong enough centralized fiscal policy as a result of nation states’ continuing hold on their fiscal sovereignty.

In this context, European competitiveness funnels directly from the competitiveness of individual nation states. Competitiveness in its strictest definition refers to the set of institutions, policies and factors that determine a country’s level of productivity. This means that competitiveness is tied to the political and social conditions in a country – and now, in Europe, it is also tied to the political and social dimensions of the crisis that I mentioned above.

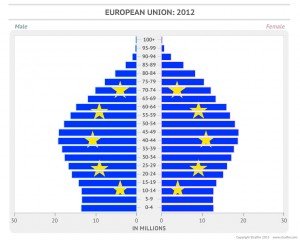

At the core of these dimensions stands the major problem that all European states now face: Bad demographics, which have a considerable impact on the resources available to create sustainable growth and competitive advantages. The effect of bad demographics on labor markets is evident. So is the implication for technology — if you have negative demographics, with shrinking and aging populations, you have to increase technological progress on your own (supporting your own industries) or find ways to benefit from technological progress made by other countries, allowing foreign investment.

The link between demographics and capital markets is less intuitive. In the following, I will refer to the relation between demographics and the cost of borrowing as a basic determinant for real economic growth. In general, mature adults provide investment capital: Their children have left home, their house is paid for, and they’re saving for retirement. Young adults are the ones consuming the capital They pay for school, they buy houses, they raise kids, and, because they are young, they are at the lower end of their earning potential. Retirees are living off their savings, and any investment coming from them is usually going into low-risk assets with minimum impact on capital markets at large and on borrowing costs.

The link between demographics and capital markets is less intuitive. In the following, I will refer to the relation between demographics and the cost of borrowing as a basic determinant for real economic growth. In general, mature adults provide investment capital: Their children have left home, their house is paid for, and they’re saving for retirement. Young adults are the ones consuming the capital They pay for school, they buy houses, they raise kids, and, because they are young, they are at the lower end of their earning potential. Retirees are living off their savings, and any investment coming from them is usually going into low-risk assets with minimum impact on capital markets at large and on borrowing costs.

Europe’s demographic trends mean that the cost of borrowing is likely to go up (unless savings rates remain high even when people retire) with the mature population going in retirement in a few years. Some countries in Central and Eastern Europe are still benefitting from growth in the mature population base, and they stand to maintain that advantage for a few more years. These countries include, for example, Poland, Romania and Slovakia. These countries’ advantage will hold if they manage to keep their youth at home and diminish migration towards the core EU countries.

Solving problems related to demographics is not easy. In general, we either get used to the idea that the retirement age will get higher, or we plan to support technological progress through investments. Since the first option is a hard sell to the European public , we also have to take investment into account as an alternative or additional policy.

For developed countries such as Germany, demographic problems are easier to manage. These countries can better attract foreign workers, and they also find it easier to invest in technology. Developing countries in the EU need to become creative. They need to support internal investment by any means, not only to encourage technological progress but also to keep the labor force at home, and they need to develop policies to encourage foreign direct investment that is sustainable for the long term.This entails investments that focus on more than project management or outsourcing and that have the potential to develop technological progress to the industrial level, supporting long term growth. National governments are responsible for designing policies and institutional frameworks to attract investment that is sustainable in the long term.

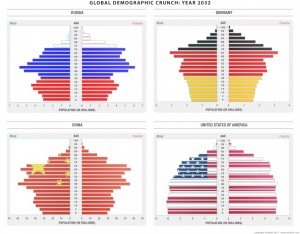

At this point all countries in Europe should be seeking to import and integrate innovation. Ideally they would import innovation from countries with a good demographic profile – technological progress will continue being funded there, as companies will still have access to cheap capital.

To compare, I selected two main groups of countries – the profile of both groups makes them potential FDI sources. The first group consists of non-European G7 developed countries: the United States, Canada and Japan. The second group is the BRICS countries: Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. Comparing their age pyramids in 2013 and in 2030, we can observe that only the United States has a continuous healthy demographic profile. Canada has money to invest now, but it will have less in the future. Japan is managing its own demographics problems. The BRICS have limited capital to spend on innovation at the moment, which is one of the reasons they’re conducting an absorption process rather than supporting technological progress. They may start having more capital available in 2050, considering the pyramids (with the exception of Russia, where demographics are not improving).

Going back to Europe, the development of economic policies should always bear in mind the social problems that the Continent is facing. To avoid increasing tensions between the elites and the general public, governments should find ways to address the single greatest problem facing Europe: unemployment. Supporting investment policies and entrepreneurship inside countries, and building an appealing environment for sustainable foreign investments, will be crucial.

Comenteaza