Last Sunday’s Super Bowl was the culmination of America’s National Football League’s sixteen game season and the playoffs that followed to determine who would win the sport’s ultimate prize–the Vince Lombardi Trophy. One of the world’s most widely watched annual television events, the Super Bowl was very disappointing to those fans wishing to see a game won or lost in the last seconds. From the opening kickoff, the Seattle Seahawks demolished the Denver Broncos delivering a 43-8 beating, one of the worst in Super Bowl history.

Last Sunday’s Super Bowl was the culmination of America’s National Football League’s sixteen game season and the playoffs that followed to determine who would win the sport’s ultimate prize–the Vince Lombardi Trophy. One of the world’s most widely watched annual television events, the Super Bowl was very disappointing to those fans wishing to see a game won or lost in the last seconds. From the opening kickoff, the Seattle Seahawks demolished the Denver Broncos delivering a 43-8 beating, one of the worst in Super Bowl history.Seattle’s defense, the best in the league, throttled Denver’s offense, also the best in football. The game was lopsided: despair for the losers and euphoria for the winners. But in a far greater and different context, the game was a metaphor for the United States and its global role.

As with the Seahawks, the U.S. has formidable defenses. And, like Denver, its offensive power is the greatest in the world. On some occasions, American policies were as decisive as Seattle’s triumph. But it also has had failures comparable to Denver’s ignominious defeat. While sport is not a substitute for politics, how might the U.S. emulate Seattle’s success and avoid Denver’s plight?

First, U.S. policy making has been diluted and distorted by political animosities that render objectivity virtually impossible. In Washington long ago, one was entitled to an opinion but not to his or her own facts. Today, opinions and facts promiscuously intermingle. The Affordable Health Care Act is a vivid example. Despite its strengths and weaknesses, the White House denies all flaws. And critics refuse to recognize benefits.

Second, tough policy choices need thorough review. Basic assumptions as well as possible consequences underlying decisions must be challenged before taking action. The second Iraq War and the Afghanistan-Pakistan (AfPak) study failed in that regard. Assumptions and actions went unchallenged. The results were predictable.

Third, the public must be informed. In this process, truth and objectivity must supersede political expediency. For example, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid who faces a tough re-election campaign opposes “fast track” trade authority. Yet one individual no matter how powerful one individual may be, the national interest must trump. Whether the Obama White House has the courage and subtly to overcome Reid’s objections remains to be seen.

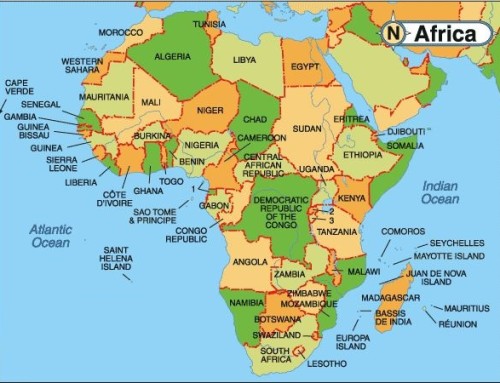

Last, unlike Denver’s first possession of the football, policy cannot tolerate fumbles. Syria is a case in point. Syria is a human tragedy in which another hundred thousand or more citizens could easily perish. The U.S. has two basic options. It can intervene. Or it can remain on the sidelines promoting a political solution and providing humanitarian assistance. Red lines and demands issued by the White House that President Assad must go were fumbles.

Intervention has several options. The U.S. could arm and train the Syrian Free Army (SFA). While that will take many months, the Assad regime and its Russian supporters would come to realize that, over time, 100,000 or more SFA well-trained and supported troops will take the field. At that stage, allied airpower could attack Syria’s air bases removing its attack helicopter and fighter aircraft advantages.

Alternatively, the U.S. could work with Russia vis a vis Iran to obtain a nuclear agreement. With that in hand, Iran might be persuaded to reduce its aid to Syria in exchange for further openings to the west. Hezbollah activities might be curtailed putting further pressure on Assad to negotiate or to stand down as president.

Neither of those possibilities appears likely. The fear of the SFA being controlled by al Qaeda or a terrorist derivative such as al Nusra makes arming the opposition a non-starter. The failure to exploit Russian cooperation in removing Syrian chemical and biological weapons renders these second likewise beyond reach.

The remaining option will be a diplomatic effort possibly with more negotiations in Geneva as the only way to achieve a ceasefire or broader political solution. That negotiation is likely to fall. Thus, the end of the civil war may only be when the civil war ends. That may take decades to happened as did the civil war in Lebanon.

Laying out these options and the consequences for the public to understand however is crucial. Then, whatever decision is made, the costs and benefits can be fully explained. Unfortunately, the White House prefers propaganda and spin to straight talk.

It is impossible to predict that future policies will yield outcomes as dramatic as Seattle’s victory or Denver’s demise. Politics is not the super bowl. The stakes are infinitely greater. Yet, the prospects for success or failure follow similar trajectories.

That President Obama favors basketball over football may preclude the relevance of this analogy. The challenge however remains. How does the U.S. win in the foreign policy super bowls in which it plays?

Comenteaza